So Much Fuss and Bother About Nothing

Those whom I offended by writing about the desirability of moving soon-to-be-unsupported Exchange 2013 on-premises servers to the cloud must have enjoyed the January 25 outage suffered by many Microsoft 365 services, including Exchange Online. Lots of hot air and annoyed words found their way across the internet to confirm everyone’s suspicions that on-premises deployments are infinitely superior to any cloud service. This could be true in some cases, but it’s not for most, even when an outage happens.

Let me explain a big fact about cloud services: outages happen all the time. And like faults that afflict on-premises infrastructures, the causes of outages come from many sources. Microsoft 365 is a highly automated operation. Even so, sometimes, the human element creates a problem, just like it can within an on-premises data center.

According to Microsoft’s post-incident report (PIR), incident MO502273 began at 7:05 AM UTC and finished at 12:43 PM UTC on Wednesday, 25 January. The formal length of the incident is five hours and 38 minutes, which is a long time waiting for engineers to resolve a problem. However, not every user within affected tenants experienced this length of the outage. The PIR is available to affected customers as a downloadable Word document through the Service Health Dashboard in the Microsoft 365 admin center. You can also read much of its content on the Azure status history page.

Many Reasons Why People Don’t Know About Outages

There’s a multitude of reasons why not everyone is affected in the same way by a Microsoft 365 outage, including:

- The design of the Office 365 infrastructure divides work across regions, data centers, and servers. A problem for a single Exchange Online server affects mailboxes connected to that server (until Exchange moves the active copy of the mailbox to another server in the Database Availability Group) while other mailboxes hum along happily. The same is true for Teams, SharePoint Online, OneDrive for Business, Planner, etc. You can work happily alongside a colleague who cannot, simply because of the resources you connect to across the internet.

- Clients like Outlook insulate users from some of the effects of network outages.

- Problems in an infrastructure component might not affect some applications. For instance, I was able to work quite happily during the incident. Traffic on Twitter and elsewhere told me about the problem, but I didn’t notice it.

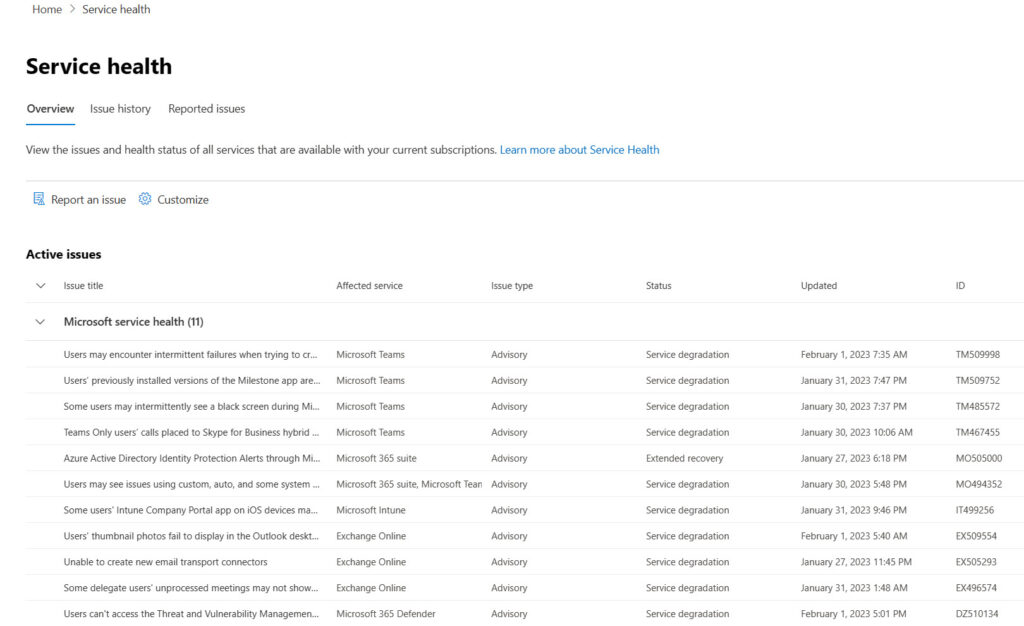

As I said above, issues happen all the time across Office 365. On February 1, the Service Health Dashboard informed me that my tenant was potentially affected by eleven separate issues (Figure 1), none of which bothered me.

Some of the issues are banal (EX509554 says that the Outlook desktop client doesn’t display user thumbnail photos). Some are more serious (TM467455 reports that calls to Skype for Business hybrid users drop after 30 seconds). My point is that we live in an imperfect world, and problems happen all the time. Despite the best efforts of Microsoft marketing, we shouldn’t expect Microsoft 365 to deliver 100% availability for every service all the time.

Microsoft Platform Migration Planning and Consolidation

Join Tony Redmond and others who are switching to the cloud with Quest Software’s Migration Solutions

No Downplaying a Serious Incident

In making this point, I don’t want to downplay the seriousness of the January 25 outage. If your business was affected by the problem, you are right to express frustration about being deprived of an essential business service. In this case, Microsoft says that a change made to their WAN impacted connectivity between:

- Internet clients (customers) and Azure.

- Connectivity across (data center) regions.

- Cross-premises connectivity via ExpressRoute.

According to the post-incident report, a planned change to update the IP address for a WAN router included a command given to the router to send messages to all the other routers. Microsoft doesn’t give details about the command or the resulting broadcast message, but it was enough to cause the routers to recompute their adjacency and forwarding tables. Given the size of the Microsoft network, this could take some time, and while the routers were busy, they couldn’t forward packets. The thing I don’t like about what Microsoft says is the comment that “The command that caused the issue has different behaviors on different network devices, and the command had not been vetted using our full qualification process on the router on which it was executed.” In other words, the engineers ran an untested command run on a critical networking component. Chaos duly ensued.

It took Microsoft about 35 minutes to figure out that MO502273 was not a DNS issue. DNS changes have been the root cause of previous Microsoft 365 outages (like outages on April 1, 2021, and May 2, 2019), so it’s unsurprising that the engineers would look in that direction first.

Thirty minutes later (8:20 AM), the engineers identified the real source of the problem and noted that ten minutes earlier automated recovery began to restore the network. By 9 AM, most network devices were stabilized and online, but the WAN didn’t recover fully until 9:35 AM. At this point, Microsoft 365 services began their recovery to restore online services to end users. By 11:30 AM, Microsoft’s telemetry indicated that most customers had service, and the incident formally closed at 12:43 PM. At this point, some customers had issues with OWA connectivity. This later evolved into a separate incident (EX502694) that took further time to resolve, eventually closing at 3:50 AM on January 26.

Issues for Microsoft

Microsoft says that they’re updating their processes to include additional safeguards that will block “highly impactful commands” from running on devices. That’s nice, but it still leaves an open question about how engineers decided to run such a command on a production router without adequate testing.

The other thing that bothers me is why Microsoft would choose to perform such an operation in the middle of the working week. I know that I’ll be told that it’s difficult to push changes to Microsoft’s data center network to weekends when any resulting problem will affect fewer customers. I’ll also probably be told that similar changes happen all the time without problems. Both arguments might be correct, but the lack of testing of the “highly impactful command” revealed the fatal flaw in the approach.

Brown Smelly Stuff Happens On-Premises Too

Could the same happen in an on-premises infrastructure? Absolutely! On-premises network administrators are not endowed with more wisdom than their cloud counterparts. The network infrastructure for an average on-premises data center is less complex than in Microsoft, but the tools and processes used to make changes are likely to be less automated too. I’ve certainly experienced the joy of an on-premises network outage due to misconfiguration. Again, problems happen in all IT infrastructures. It’s just that any error in the cloud is magnified enormously because of the sheer number of people impacted by an outage.

No Impact on SLA

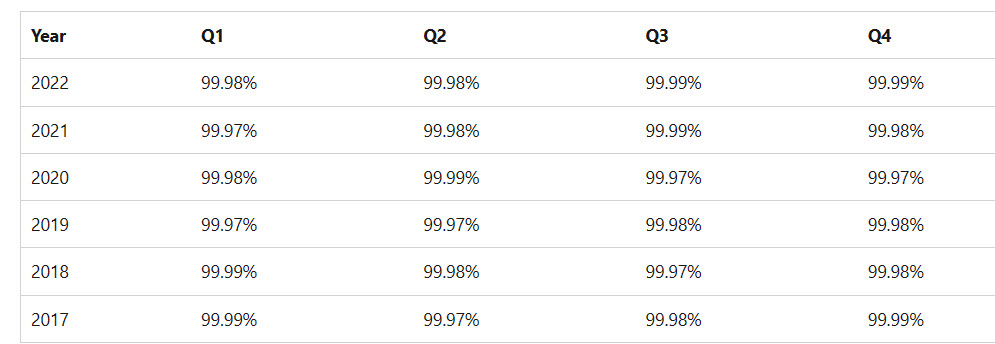

Microsoft offers a financially-backed service level agreement for its cloud services, with compensation available to customers if the service achieves less than its 99.9% commitment. Its website lists recent SLA worldwide performance for Microsoft 365 (Figure 2).

The worldwide figures for SLA performance are excellent for the 2017-2022 period. The experience for an individual tenant might vary due to factors like its data center region and the faults within that region, which affect the workloads used by the tenant. Given the sheer size of Microsoft 365, the chance that individual outages will affect performance against SLA unless the outage extends across multiple regions and affects hundreds of millions of users.

In the case of the January 25 outage, no one knows how many users the incident affected. We do know the number of minutes the incident lasted, but that’s not the same as downtime minutes, defined for different workloads in the Microsoft Online Services SLA. For instance, for Exchange Online, the definition is “Any period of time when users are unable to send or receive email with Outlook Web Access.” In other words, downtime is when people can’t use a service rather than the length of an incident. Even if the full length of the January 25 outage counted as downtime, its impact on the SLA is determined by the count of affected users. For instance, if the incident affected 7.5 million users, it barely budges the SLA needle.

| Outage (minutes) | 338 |

| Users affected | 7,500,000 |

| Minutes lost in incident | 2,535,000,000 |

| Total available minutes (January 2023) | 44,640 |

| Office 365 Users | 375,000,000 |

| Total Office 365 Minutes | 16,740,000,000,000 |

| Impact of outage | 0.0151% |

| Uptime percentage | 99.98% |

It will be interesting to see the SLA result for Q1 CY23 that Microsoft publishes in mid-May (it normally takes six weeks after the end of a quarter for the data to appear online). I don’t expect that many, if any, customers will be able to take advantage of service credits because of the outage.

But Back to the Point

We’ll experience more Microsoft 365 outages in the future, and much the same hot air will flow. It’s the nature of the beast. But an outage or two (or maybe even three) doesn’t mean that cloud services are bad. I moved from on-premises servers in 2011 and haven’t looked back. The journey has been interesting, frustrating, and irritating at times, but I really don’t regret not having to apply cumulative and security updates to servers. Nor do I want to secure my Exchange and SharePoint servers against external attacks. Unless you’ve got a good business need to stay on-premises, the cloud’s better for utility services like those delivered by Microsoft 365.

Microsoft Platform Migration Planning and Consolidation

Join Tony Redmond and others who are switching to the cloud with Quest Software’s Migration Solutions