Make Sure People (Including Attackers) Aren’t Signing into Break Glass and Utility Accounts

A reader asked about a script they’d found that purports to defend against hackers taking over break glass accounts by running scheduled searches against the unified audit log and asks if this seems like a good idea. My response was that the idea seems reasonable in principle but is flawed on several fronts.

Problems with the Reported Solution

First, although it’s true that break glass accounts (or emergency accounts in Entra ID parlance) are both highly privileged and not protected by conditional access policies, their authentication arrangements are usually sufficient to defeat even the best attacker. It’s common practice to give these accounts the most obscure and long passwords (written down and secured in a locked box or similar arrangement) backed up with a strong secondary authentication method, like a FIDO2 security key or passkey.

Second, if an attacker compromises the break glass account, the tenant is in a world of hurt because the attacker has possession of a highly privileged account. It’s likely that the attacker will attempt to neutralize any detection and reporting processes as quickly as possible. Skilled attackers have toolkits to comprehensively infect a tenant very quickly, so reporting a problematic sign-in event is the least of administrative challenges following the compromise of a highly privileged account.

Speed is important when detecting signs that bad things might be happening. Each time a sign-in attempt occurs, Entra ID captures details of the (successful or failed) event in its sign-in audit log. Events are available for querying soon after. Sometime later after an Entra ID sign-in happens, the unified audit log ingests the event from Entra ID. The time lag creates a period for the attacker to find and stop reporting or to perform other undesirable actions, like data exfiltration.

Microsoft doesn’t guarantee how long it will take before an event shows up in the unified audit log. Guidance used to be given which said that user login events could take up to 24 hours. Although sign-in events do show up more quickly than 24 hours, you cannot depend on when those events are available in the unified audit log. For this reason, it’s always best to query the Entra ID sign-in log.

Deciding on the best interval between checks is a matter of balance. You don’t want to be paranoid, but you do want to detect problems as soon as possible. Choosing the interval between checks is a compromise between frequency and effectiveness.

The downside of using the Entra ID sign-in logs is that searching sign-ins using an API or cmdlet requires the tenant to have Entra P1 licenses. A small payment might also be required for Azure Automation (see below). If the tenant has Purview audit licenses, no payment is necessary to perform a synchronous or asynchronous audit log search.

Third, the solution uses the Windows Task Scheduler to run a PowerShell job to check the unified audit log. Using Windows Task Scheduler introduces a further dependency because the workstation where the job is scheduled to run might be offline or otherwise prevented from executing the job. I do not recommend using Windows Task Scheduler for important Microsoft 365 PowerShell jobs. Using managed identities for script authentication with Azure Automation is a more secure and reliable method than depending on user credentials and Task Scheduler. Windows Task Scheduler is an outdated and unstable platform that should only be used when no other alternative is available.

A Better Solution

To solve the problems outlined above, let’s discuss how to build a monitoring job that checks for unexpected sign-ins to utility accounts. I define a utility account as an Entra ID account that isn’t typically used for day-to-day activities. Any sign-in to one of these accounts is an out-of-the-ordinary occurrence that deserves administrator oversight. You can make your own assessment of what is a utility account.

As examples for this discussion, I use break glass accounts together with the accounts created for Exchange Online room and shared mailboxes. The reason for the latter is that these accounts are designed to operate without user sign-ins and if someone signs into the account for a room or shared mailbox, they might violate the Exchange Online service agreement.

Marking Accounts to Check

One of the issues that exists in Entra ID is that no differentiation exists between tenant member accounts that are used by real people and those used for utility purposes. To mark the accounts to monitor, I decided to use a custom attribute and mark utility accounts with “Utility” and break glass accounts with “BG.” Here’s how to use the Set-Mailbox cmdlet to update the custom attribute for shared and room mailboxes. The dual-write mechanism used by Exchange Online ensures that Entra ID also updates the attribute.

Get-Mailbox -RecipientTypeDetails SharedMailbox, RoomMailbox, EquipmentMailbox -filter {CustomAttribute1 -ne "Utility"} | Set-Mailbox -CustomAttribute1 "Utility"

Break glass accounts probably don’t have mailboxes, so the Update-MgUser cmdlet does the job instead. I use a different code to allow for differentiation between different types of utilty mailboxes:

Update-MgUser -UserId BGAccount1@office365itpros.com -OnPremisesExtensionAttributes @{'extensionAttribute1' = "BG"}

Now that all the accounts are marked, they can be found by a filter applied with the Get-MgUser cmdlet:

[array]$UtilityAccounts = Get-MgUser -Filter "(onPremisesExtensionAttributes/extensionAttribute1 eq 'BG' or onPremisesExtensionAttributes/extensionAttribute1 eq 'Utility') and userType eq 'Member'" -All -PageSize 250 -ConsistencyLevel eventual -CountVariable Records

Sketching Out the Solution

With the accounts marked, we can proceed to build the solution. I chose to:

- Create a PowerShell runbook (script) to run on an Azure Automation schedule.

- Connect to the Graph with a managed identity.

- Find the set of accounts to check.

- For each account, check the Entra ID sign-in log using the Get-MgAuditLogSignIn cmdlet.

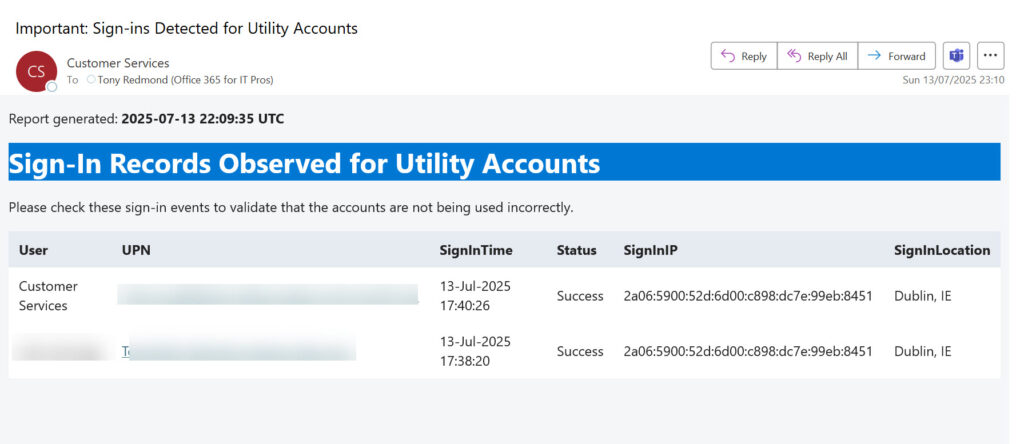

- If any sign-in events are found, the runbook sends email to administrators (Figure 1).

Preparing the Runbook

Azure Automation accounts must be prepared to run Microsoft Graph PowerShell SDK scripts. SDK cmdlets are divided over a set of modules, and the modules containing the cmdlets used in the runbook must be loaded as resources into the account. In addition, the service principal for the automation account must be granted the permissions to run the cmdlets. Here are the required permissions:

- Mail.Send: Send email. This cmdlet allows access to every mailbox in the tenant, so consider using RBAC for applications to restrict its scope.

- User.Read.All: Read details of user accounts, specifically basic details like the display name plus the extension attributes.

- AuditLog.Read.All: Read the Entra ID sign-in audit log.

The runbook uses the following modules:

- Microsoft.Graph.Authentication: Run the Connect-MgGraph cmdlet to authenticate and get an access token

- Microsoft.Graph.Users: Run the Get-MgUser cmdlet to fetch the set of utility accounts.

- Microsoft.Graph.Users.Actions: Run the Send-MgUserMail cmdlet to send email if problems are found.

- Microsoft.Graph Reports: Run the Get-MgAuditLogSignIn cmdlet to search the Entra ID audit log.

See this article for details about how to load modules and assign permissions for Azure Automation accounts.

I used version 2.29 of the Microsoft Graph PowerShell SDK and the V5.1 PowerShell runtime. The runbook code follows the structure outlined above. After finding the set of utility accounts, the Get-MgAuditLogSignIn runs to check if accounts have sign-ins. Entra ID only holds sign-in audit log records for 30 days whereas after ingestion into the unified audit log, the sign-ins are available for 180 days (Purview audit standard) or 365 days (premium). Given that we want to discover sign-ins as soon as possible after they occur, the 30-day threshold is not a limitation.

Here’s the code to find if any sign-ins exist. You can see that the code fetches only one sign-in. To fetch more, remove the -Top 1 parameter and Entra ID will return up to 1,000 records. One reason to return more records is that failed sign-ins could indicate when attempts are being made to access an account:

Try {

UserId = $User.Id

[array]$SignIn = Get-MgAuditLogSignIn -Filter "userid eq '$UserId'" -Top 1 -ErrorAction Stop

} Catch {

Write-Host "Failed to retrieve sign-ins for user $($User.displayName): $($_.Exception.Message)" -ForegroundColor Red

Continue

}

After processing all the utility accounts, the code checks if any sign-ins were found and if some exists, it generates and sends an email to advise administrators about the issue.

You can download the full script from GitHub. The same code runs interactively or as an Azure Automation runbook.

Scheduling the Runbook

When the code runs as expected, publish the runbook to make it ready for scheduling and then follow the steps contained in this article to schedule the runbook to execute at whatever frequency you deem appropriate.

Each time the runbook executes, it consumes some runtime. Microsoft allows tenants 500 free runtime minutes monthly for process automation (including runbooks) and afterwards applies a charge of $0.02 per minute against an Azure subscription. A runbook like the one discussed here will cost very little, even if run multiple times daily.

Overcoming Inertia

Like any code that you find on the internet, some thought needs to be applied before accepting that the code as presented is the best way to perform a task. We all have personal biases, and developers often cling to a way that they know rather than finding a better or more effective method of retrieving data. It’s a natural desire to get a task done instead of considering new approaches that will take longer. Inertia takes a lot to overcome.

I’m sure that the original solution works, but it does seem that a better method exists in this case. And above all, please do get rid of Windows Task Scheduler.