Managing OAuth2 Applications is an Important Task for Microsoft 365 Administrators

At times, it seems like seeing threat in OAuth2 applications is the new crusade for Microsoft 365 tenants. Based on the solemn pronouncements I see from Microsoft MVPs (some supporting ISV attempts to sell products), tenants must be facing a catastrophic wave of infected and malign apps. But reality is different and a more measured approach should be taken. You don’t need to invest in expensive products to manage the apps in your tenant, but it’s wise to keep a wary eye on what those apps are used for and check on a regular basis.

Practical365.com has long advocated for better app management. As we approach fifteen years of Office 365, it is strange that Entra ID doesn’t include some form of app inventory or way to highlight high-priority application permissions like Mail.Send, Mail.Read, Sites.Manage.All, and Files.Read.All that attackers might use to exfiltrate data from user mailboxes, SharePoint sites, and OneDrive for Business accounts. We also recommend that any app that accesses user mailbox content should be governed by RBAC for Applications. Perhaps the Entra team will create a Copilot agent to help tenant administrators analyze and manage the permissions assigned to registered and enterprise apps.

An agent to detect and suppress malicious apps would have been very useful during the Midnight Blizzard attack when attackers managed to exfiltrate lots of confidential information from Microsoft’s own tenant. Alas, that attack happened in March 2024 before the agentic wave that now embraces everything in Microsoft 365.

Looking for Malware Apps

An AI-infused agent isn’t needed to perform an initial analysis of the apps and service principals that exist within a tenant. This thought came into my mind when I read the October 20, 2025 BleepingComputer article about how to find malicious OAuth apps. The author provides a hunting tool called Cazadora (available from GitHub) to search for bad apps.

The author is Matt Kiely, who works for Huntress Labs, which offers products to help companies secure their infrastructure. According to the text, Huntress checked over 8,000 Microsoft 365 tenants from different verticals and industries to collect details of the enterprise apps and app registrations found in the tenants. They analyzed the data to present their findings at a conference about a year ago (see the YouTube video).

Some of the findings are startling, such as 10% of the tenants had a well-known “Traitorware” app in place. The conclusion reached is that OAuth App Attacks “are way more prevalent than we anticipated. Some of these apps had been around for years by the time we uncovered them.” The author goes on to assert that “statistically speaking, there’s a good chance that your own tenant is infected with one of these apps.”

The Cazadora code is written in Python, which isn’t my thing. But it’s easy enough to see that it checks for:

- The Traitorware apps.

- Apps with “Test” in their name.

- Apps named after users (display name or user principal name).

- Apps with names formed from non-alphanumeric characters.

- Apps with suspicious reply URLs (based on ProofPoint’s MACT 1445 campaign).

Crafting an Analysis Script with PowerShell

How hard would it be to write a PowerShell script to hunt for problem apps (and more)? The answer is, not too difficult, if you know your way around the Microsoft Graph PowerShell SDK and how Entra apps work. Let’s discuss what a script might do:

- Some initial setup is required to connect to the Graph with the correct permissions and build arrays containing details of Graph permissions, known bad apps, and the high-priority permissions that should be tightly controlled.

- Run the Get-MgServicePrincipal cmdlet to fetch all service principals known in the tenant. Many service principals belong to first-party apps that are controlled by Microsoft. However, it’s good to keep an eye on this data because tenants can accumulate app debris introduced by Microsoft and other ISVs over time.

- Loop through the service principals to gather and analyze information about enterprise apps (like the first-party apps) and app registrations (the apps created and owned by the tenant). Apart from checking for the same issues as Cazadora looks for, the script also checks for expired credentials held by apps (app secrets and certificates) and application and delegated permissions assigned to service principals. Suitable warnings are flagged if anything is discovered that administrators should review and perhaps address.

- When it processes a service principal, the script uses the Find-MgTenantRelationshipTenantInformationByTenantId cmdlet to resolve the owning tenant identifier to the display name of the Entra ID tenant that owns the enterprise app. This is how we can tell if an app is a first-party Microsoft app, an app from other notable companies like Apple or Adobe or belongs to an ISV. Sometimes, an app that seems to be used by Microsoft functionality is owned by the company that created the app on behalf of Microsoft. This shouldn’t happen because Microsoft should own apps that it distributes to customers, but I found apps called “Microsoft Tech Community Stage” and “O365-CC-Export” generated by a tenant called PRDTRS01.

- The script also reports if an app comes from a verified publisher. A verified publisher is a company that has gone through the Microsoft 365 app certification process.

- Create an output CSV or Excel worksheet (the Excel worksheet is generated if the ImportExcel module is available) and send it to the destination address defined in the script (any valid email address can be used).

My version of the Service Principal Analysis report script is available from GitHub. This is a good example of the kind of periodic check that is well suited to running as a scheduled Azure Automation runbook.

Discovering Unused Service Principals

Many old and unused service principals are often found in tenants. I wanted to get some idea about active and inactive service principals.

Two methods are available to check service principal activity. The first is to use Entra ID audit log sign-in records. These records are available for the last 30 days and can tell how often a service principal has been in use during that period. The downside is that retrieving audit sign-in records from the Graph requires Entra P1 licenses. It’s also quite expensive in processing terms to find and report these events.

The faster option is to use the Graph servicePrincipalSignInActivity objects. The activity object for a service principal includes a timestamp for the last successful sign-in. By fetching the sign-in data and loading it into a hash table, the script can quickly discover the last time a service principal was used. The only downside is that a successful sign-in record might capture the only such event for a service principal.

If it’s important to know how many times a service principal recently signed in, it would be possible to update the script code to include both checks.

What You Can Expect to Discover

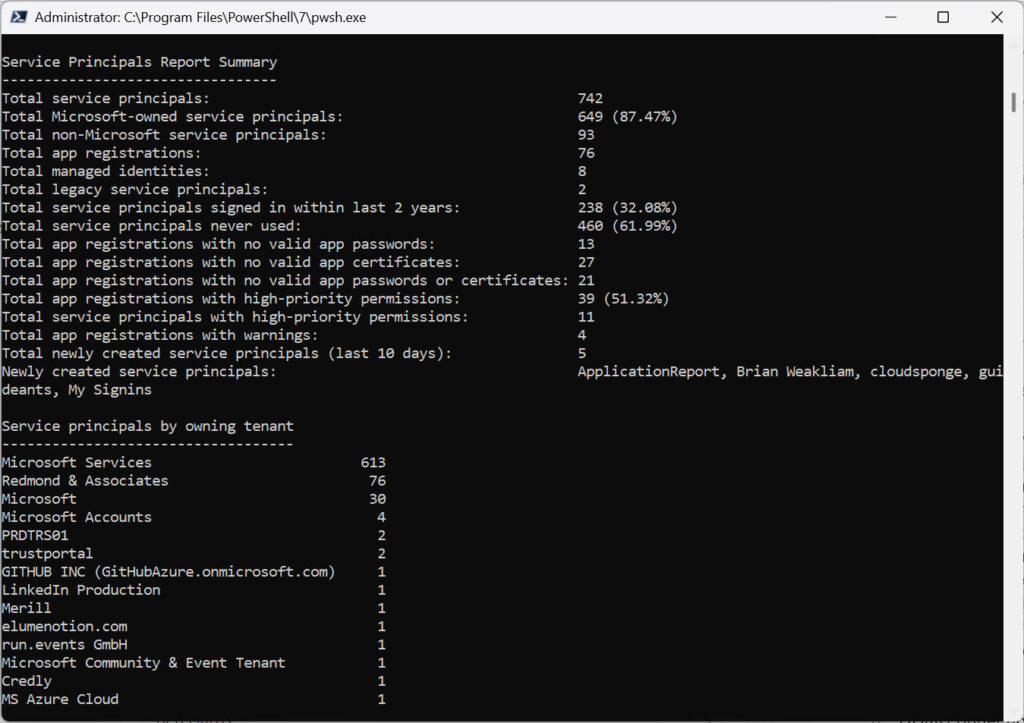

Figure 1 shows the results reported by the script for a run in my tenant. The tenant has been in existence since 2011, so there’s certainly been the opportunity to acquire apps over the years.

You can immediately see that the majority of the service principals belong to Microsoft or Microsoft-associated companies. I don’t know why Microsoft splits enterprise apps across the Microsoft Services, Microsoft, and Microsoft accounts tenants. The Microsoft Community & Event tenant is responsible for an app called Community Days that’s never been used, while the MS Azure Cloud tenant owns the EngineeringHub app created in February 2025 and not used since.

Another app comes from Merill Fernando’s tenant (Identity Power Tools), probably created to run the conditional access documentation app, while others come from well-known companies like LinkedIn, GitHub, and Credly. Another app is from run.events GmbH (the team behind the European Collaboration summit and other events) to allow event speakers to propose sessions for events.

The trustportal tenant appears to have been used to access documents in the Microsoft Service Trust Portal from features like Office 365 Secure Score. There is a second (newer) Office 365 Secure Score app owned by Microsoft Services. The other trustportal app is called O365TrustPortal and dates from 2015. I suspect that this is an example of Microsoft not cleaning up enterprise apps created in customer tenants after moving a feature from preview to production status. Both apps can be removed.

The two apps reported for the PRDTRS01 tenant are discussed above, and the elumenotion.com tenant is the one hosting the GuideAnts app that I allowed into my tenant in error.

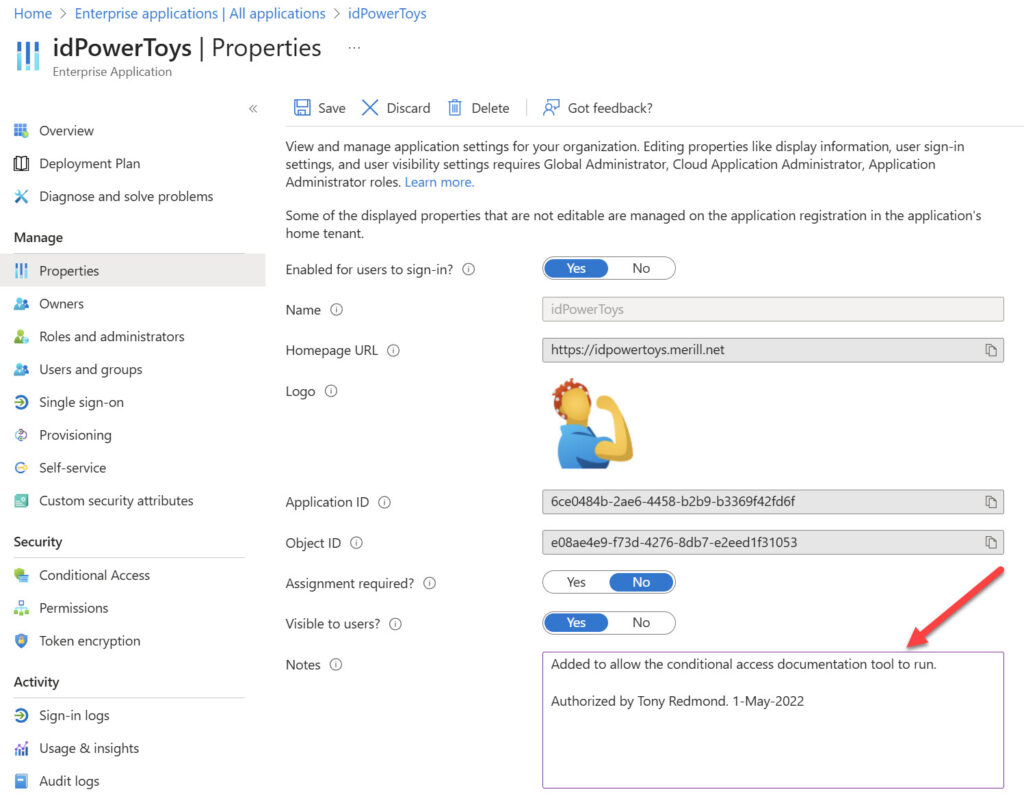

All of this proves that a variety of apps can show up in a Microsoft 365 tenant. Administrators should be able to account for non-Microsoft enterprise apps. I suggest that it is good practice to tag service principals after they’ve been added with a note explaining their purpose, and perhaps even a contact name (Figure 2). Apart from being able to include the notes in reports, they’ll trigger a memory for administrators during reviews.

Understand Your Service Principals and Apps

Like anything else in Microsoft 365, something that seems complicated and obtuse isn’t so bad when attention is paid to understanding what’s happening and what the data reveals. Reporting and reviewing service principals and apps regularly is a good way to keep this aspect of tenant management under control. Hopefully the script proves to be a good starting point for the task.

I’m glad to walk trough about it. Indeed, there are lot of application(s) get registers and there is no way forward to track them or their permission.

Is there any other way do we have than running the script?

You could check apps and service principals through the Entra Admin Center. That will quickly get boring, which is why I used PowerShell to automate the process.