Price Increase from July 2026 Makes It Important to Check Licenses

Last month, Microsoft 365 tenants received seven months’ warning for license price increases from July 1, 2026. Some licenses, like Microsoft 365 Business Premium, remain unchanged, but common enterprise licenses are all increased. Office 365 E3 goes up by $3/month to $26 while Microsoft 365 E5 also increases by $3 to $60/month.

In some cases, Microsoft is adding new functionality to offset some of the pain. For example, an announcement at the Ignite 2025 conference laid out plans for Microsoft 365 E5 to include Security Copilot during 2026, including a monthly allocation of Security Compute Units (SCUs) dependent on the number of E5 licenses in the tenant.

Microsoft last increased its license prices in 2022, so it might be that we’re on a four-year increase cycle. However, given the amount of investment Microsoft is making in datacenter capacity to host AI and other growth, the temptation might be to push increases through at a faster cadence to keep Wall Street happy.

Conduct a Annual Licensing Audit

All of which brings me to the subject of an activity that should be an annual event for Microsoft 365 tenants: the annual licensing audit. I realize that dealing with licensing is an activity analogous to a dental extraction in the minds of some, but that doesn’t get away from the point that it’s easy to overspend on Microsoft 365 licenses.

Microsoft won’t check that tenants have the most efficient combination of licenses. It’s in their interest to sell more licenses and pick up the monthly charges that flow in from unused or unnecessary licenses. In any case, Microsoft doesn’t know about the business challenges and requirements that can influence license purchasing. The licensing audit is definitely a tenant-specific activity.

My approach to license auditing spans four stages:

- Inventory: Discover what subscriptions exist in the tenant and which accounts are assigned which licenses. The Microsoft 365 licensing report script is a good starting point. The latest version of the script provides analysis of licensing cost per user, department, and country. Commercial products are also available to generate licensing analyses. Use whatever makes sense to you to extract as much information as possible about who’s got licenses and how they use their assigned licenses.

- Question: Look for inefficient license use. For example, if someone is assigned a Microsoft 365 Copilot license ($360/year), you’d expect to find evidence that they use Copilot in applications. Audit and usage data can help answer the question about who’s using Copilot or any major application. All it takes is some PowerShell and persistence. Spend $10/month on GitHub Copilot and you’ll find it much easier to work with licensing data via PowerShell.

- Adjust: Based on facts rather than feelings, decisions about the appropriate license mix are better informed. It’s possible that different licenses might be needed to swap out for inefficient licenses. For instance, people who do a lot of work with Purview solutions can be better off with Microsoft 365 E5 licenses rather than Microsoft 365 E3 and some Purview add-ons. After deciding on the appropriate license mix, make the adjustments to remove or reassign licenses and wait for the wails of pain in protest. Some user complaints about license removal will be justified and should be actioned; most will have no evidence to back assertions that a certain license is required.

- Document: As noted above, the licensing audit should be an annual activity. Starting from scratch every year doesn’t seem like a great plan. Document the data used to establish the baseline in an audit and base the next audit on that baseline. It will make decisions to purchase or decommit from licenses much easier.

None of this is rocket science. It’s just common sense with a helping of business awareness (some licenses are needed for specific business purposes) and audit and usage data found in Microsoft 365. Because Microsoft removes audit and usage data after a period (for example, Purview keeps audit data for 180 days for E3 accounts), it’s wise to keep whatever data is used for the audit in a separate repository that you control.

Check Self-Service Purchases and Add-On Licenses Too

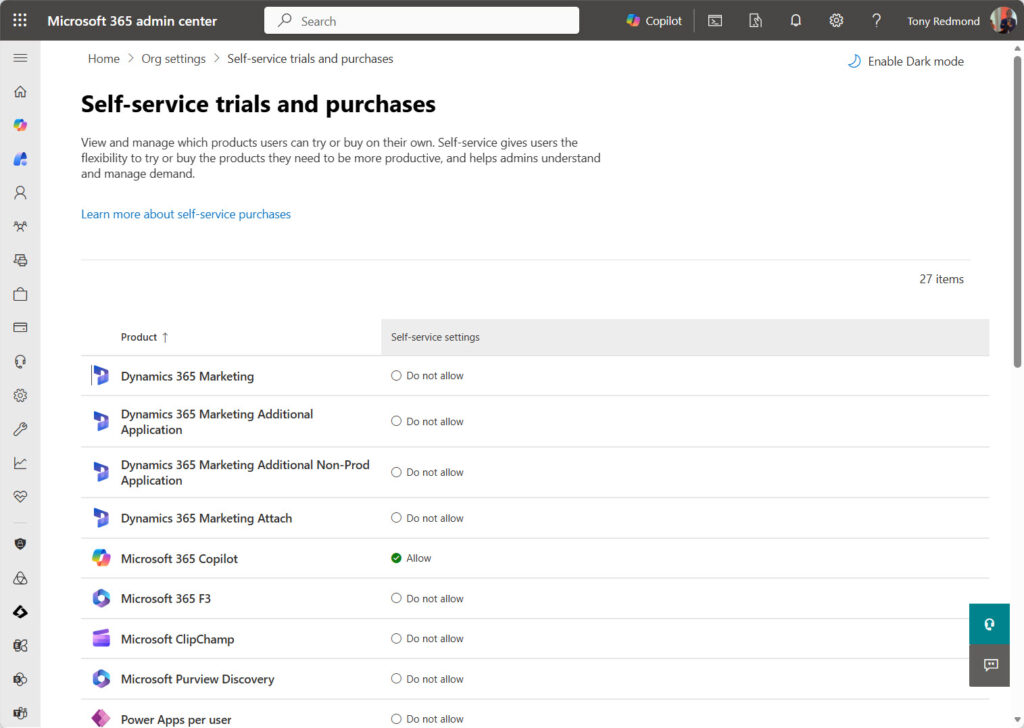

Prices are going up everywhere and it’s easy to ignore a price rise scheduled for six months away. But licenses have a nasty habit of remaining in situ within tenants, including the add-on licenses purchased for a specific project or licenses bought by end users through Microsoft’s self-service purchasing mechanism (Figure 1). People will keep licenses long after the business need to use something like Project Plan 3 or Power BI Pro passes.

Navigating License Checks in Software Audits

Apart from anything else, documenting license usage within a tenant is great preparation for commercial discussions with Microsoft, including if Microsoft decides to audit a tenant to make sure that license usage is in accordance with the rules set down in service descriptions. Audits aren’t fun, but they are a lot better if you’re well prepared. The Microsoft personnel who conduct software audits are human, so they make mistakes like anyone else. Knowing exactly what licenses are in place and how the licenses are used means that it’s possible to have an intelligent discussion instead of accepting everything Microsoft says.

The licensing requirements in Microsoft service descriptions can change over time. A recent change altered the requirement for a Microsoft Defender for Office 365 (MDO) license for every shared mailbox in a tenant once an E5 license is present and MDO is active. The latest guidance is that only shared mailboxes that benefit from MDO processing (i.e., accept or send external email) need to be licensed, and it’s sufficient for the tenant to have licenses instead of assigning the licenses to the mailboxes.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line is that tenant administrators are responsible for managing software licenses. Someone else might buy or fund the licenses, but administrators assign and maintain the licenses in use. Handing free money for unused or unwanted licenses to Microsoft has never seemed to be a particularly intelligent pursuit. As license prices climb, that pursuit becomes even less intelligent. Do yourself a favor and run an annual licensing audit. You know it makes sense.