Extending the Usefulness of Sign-in Audit Data

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how to use the Entra ID audit sign-in logs to understand how users and applications interact with Entra ID. It’s the kind of knowledge that helps Microsoft 365 administrators understand how their tenants tick.

Today, I’m going to take a slightly different approach by combining sign-in data with the last sign-in date for user accounts to generate a report about when users last signed in successfully and the apps they use. After all, understanding that someone can sign into a tenant successfully is valuable; knowing what apps they use can be even more important.

Discovering the Apps People Use

First, let’s get some information about the apps detected in user sign-ins. This code fetches the latest 20,000 sign-in audit logs and counts the number of instances for each app. I’m showing the top eight apps found in my tenant. Remember, Entra ID keeps sign-in records for 30 days and that the data shown here is purely for illustrative purposes. What you see in your tenant will reflect the apps people use, how they access those apps, and how often users are required to sign in.

[array]$SignIns = Get-MgAuditLogSignIn -Top 20000 -PageSize 500 $SignIns | Group-Object AppdisplayName -NoElement | Sort-Object Count -Descending | Format-Table Name, Count Name Count ---- ----- Microsoft Teams 7006 Microsoft 365 Security and Compliance Center 1933 Microsoft Edge 864 Microsoft Exchange Online Protection 853 Microsoft Edge Enterprise New Tab Page 842 Office365 Shell WCSS-Client 695 Augmentation Loop 625 Office 365 Search Service 622

It’s normal to see a lot of sign-in activity for Teams. Every hour or so, because their access token expires, Teams clients renew the access token and sign in automatically to keep users connected. Among the other apps, we see a lot of client activity through the Edge browser and lots of interaction with the Purview compliance portal, which accumulates sign-in events as users access the various Purview solutions.

The Office365 Shell WCSS-Client is worthy of common. This is a very common entry in any analysis of sign-in data because the shell client (also known as the suite header) is code that runs whenever a user navigates between Microsoft 365 applications in a browser. It does things like retrieve information about the licensing state for the signed-in user to allow the app launcher to restrict its display to apps that the user is entitled to access. It also connects to the user’s Exchange Online mailbox to fetch details of upcoming events and notifications, and to the Microsoft Graph to retrieve user settings like the browser theme. The app also fetches information about the most recently used (MRU) list for the user. Because users commonly navigate from app to app during a session, several events for the client can show up in the sign-in audit log as the shell client fetches and caches different information from different workloads.

Modifying App Names

Now that we know the frequency of app sign-in, we can create a list of the apps found. The reason to do this is that some of the app names are not obvious (like the shell client). By exporting the app data to a CSV file, we can edit the app names to make them more understandable. Here’s what we do to create and export the CSV file:

$Apps = $SignIns | Sort-Object AppId -Unique

$AppInfo = [System.Collections.Generic.List[Object]]::new()

Foreach ($App in $Apps) {

$ReportLine = [PSCustomObject][Ordered]@{

'App' = $App.AppId

'Name' = $App.AppDisplayName

}

$AppInfo.Add($ReportLine)

}

$AppInfo = $AppInfo | Sort-Object Name

$AppInfo | Export-Csv c:\temp\AppInfo.CSV -NoTypeInformation

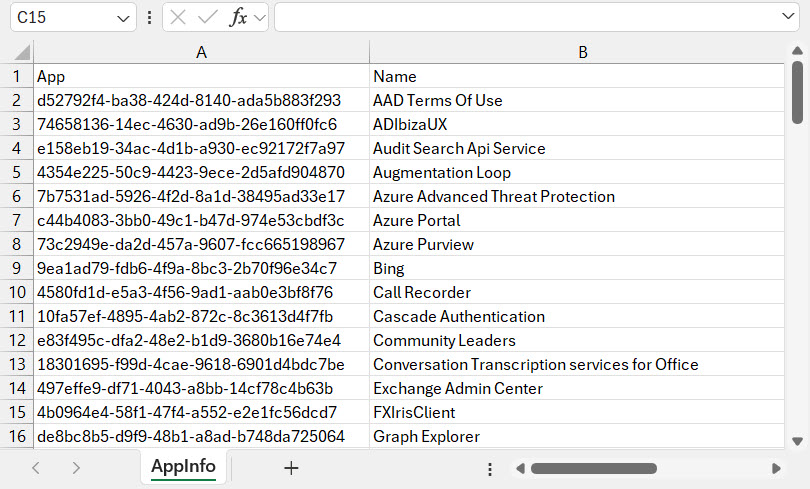

I normally edit the app file with Excel (Figure 1) and scan through the names to see if I can replace any with better names. Microsoft documents first-party apps and their identifiers, but the information available online is incomplete and doesn’t cast any more light on what many of the apps do. To be fair to Microsoft, the engineers who named the apps probably didn’t set out with the intention of making the intention behind the apps very obvious.

After customizing the app names, we can load them into a hash table for lookup by the script with code like this:

$AppDataAvailable = $false

$AppDataFile = 'C:\temp\AppInfo.csv'

If (Test-path $AppDataFile) {

$AppDataAvailable = $true

[array]$AppDataInfo = Import-CSV $AppDataFile

$AppDataHash = @{}

ForEach ($App in $AppDataInfo) {

$AppDataHash.Add($App.App, $App.Name)

}

}

The Main Script

The main script, which you can download the script from GitHub finds the set of licensed Entra ID user accounts, excluding any Exchange Online shared and room mailboxes that have licenses, and does the following for each account:

- Finds the last successful sign in date, or if this property is unavailable, the last sign-in date.

- Calculate how many days it’s been since the last sign-in. If this is 30 or less (the maximum range for Entra ID audit sign-in records), the script fetches the last 50 sign-in events. If you consider that this isn’t enough to create a good analysis, you can increase the number of fetched events. Doubling the number will increase the time required to process each account by 1-2 seconds.

- Finds the set of unique application identifiers from the set of sign-in events and checks each identifier against the hash table of app names to build the set of apps the user has signed into.

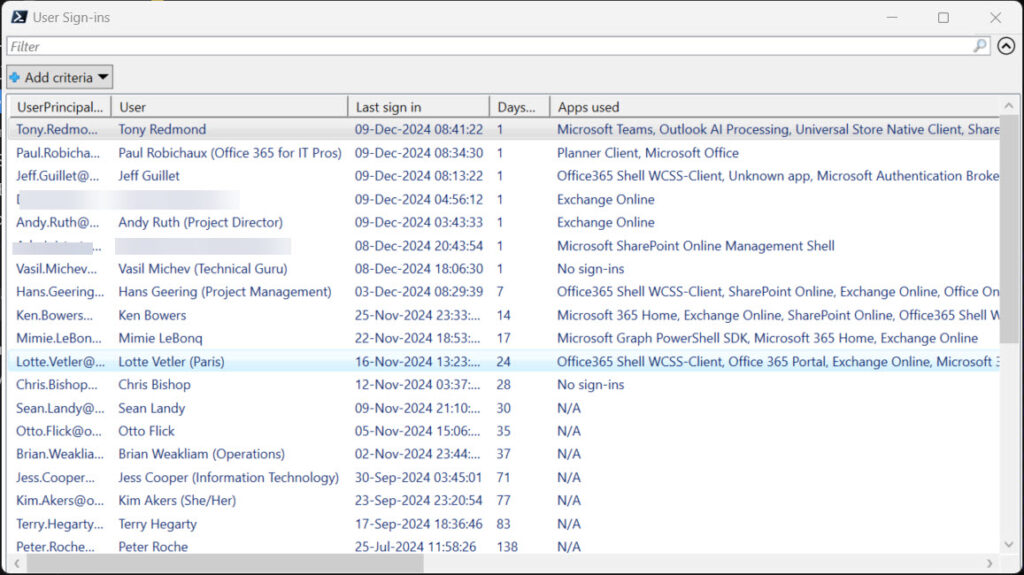

After extracting the various bits of data to construct a report, the script sorts the data by the last sign-in date and outputs the result through the Out-GridView cmdlet (Figure 2) and either an Excel worksheet or CSV file, depending on whether the ImportExcel module is installed on the workstation.

The result is that we now know the last sign-in dates for user accounts together with the most recent applications they have signed into. Checking audit logs makes it slower to report user sign-ins, but I think the extra data is worthwhile.

Audit Logs for Non-Interactive Sign-ins

The Get-MgAuditLogSignIn cmdlet returns data for interactive sign-ins. User accounts can also be used for non-interactive sign-ins, such as when they are used to run a scheduled Power App flow. To find details of interactive sign-ins for a user account, use the Get-MgBetaAuditLogSignIn cmdlet and specify the “interactiveUser” event type. To find non-interactive sign-ins, look for events that are not of that type. For example:

[array]$AuditSignIns = Get-MgBetaAuditLogSignIn -Filter "userId eq '$UserId' and (signInEventTypes/any(t:t ne 'interactiveUser'))" -Top 50

Make sure to use the account identifier rather than the user principal name for this kind of lookup.

Building a Picture

When I discuss the topic of using PowerShell to manage Microsoft 365 at conferences and other events, I often discover that people are very focused on exploiting a single data source and don’t think about how they can combine information from multiple sources to construct a more complete picture. They also accept whatever data Microsoft makes available. There’s no doubt that valuable insight can be gained from individual data sources, but it’s often better when you cast a net more widely, like we did here.