Windows 11 TPM Requirement in Context

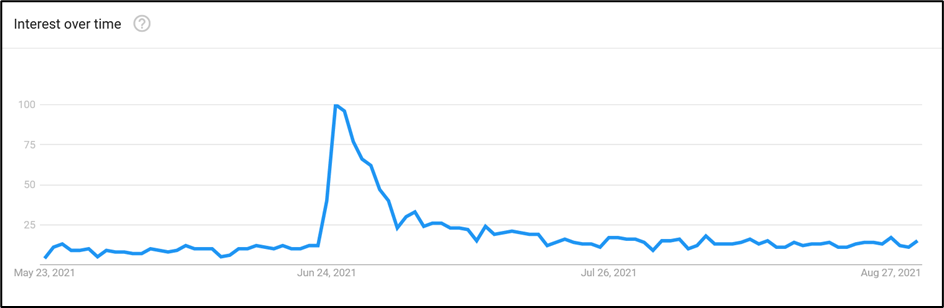

In June of 2021, Microsoft announced the requirements for Windows 11. In contrast to the requirements of Windows 10, Windows 11 has a notable security hardware requirement: to install Windows 11, PC configurations must include version 2.0 of the Trusted Platform Module (TPM). Interest in why Microsoft wants PCs to have TPM 2.0 immediately skyrocketed:

Now eight months after the Windows 11 announcement and five months removed from its general release, this article outlines the benefits of TPM and examines to what extent the requirement will protect devices from the most common threats.

What are TPMs?

Using dedicated (‘discrete’) or integrated hardware, Trusted Platform Modules have, since 2003, guarded cryptographic secrets. The TPM specification, managed by the Trusted Computing Group (TCG), has matured over time to protect against vulnerabilities and follow trends in acceptable security practices.

For example, evidence emerged that the SHA-1 hashing algorithm of TPM 1.2 might be vulnerable in proof-of-concept attacks. With the move to TPM 2.0 in 2014, the algorithms ceased to be defined in the standard, so manufacturers could introduce new ones to improve security without revising the standard. Originally, Windows 11 had a ‘hard floor’ requirement of TPM 1.2, but Microsoft subsequently decided to use TPM 2.0.

TPM can also achieve certain things using hardware that software simply cannot achieve. For example, a risk exists where attackers can compromise an operating system to access objects in memory. The TPM has memory that cannot be accessed even by the OS, which secures it against manipulation and sniffing. The Platform Crypto Provider in Windows creates cryptographic keys to be stored in the TPM, and Windows can then access the keys without storing them in its memory. To protect against brute-force attacks, TPM also benefits from automatic locks on repeated failures, and an optional capability to block key exports.

TPM in Windows

Previous versions of Windows (including Windows Server) could use TPM, even if not a hard requirement. Microsoft just required OEMs of Windows 10 and Windows Server 2016 devices to include TPM 2.0 if they wanted Microsoft endorsement of their support for Windows running on their hardware.

Now, let’s look at how TPM is used across Windows in both obvious and not-so-obvious ways.

BitLocker

The first way most IT pros experience TPM is through BitLocker, Microsoft’s enterprise disk encryption offering. Without a TPM, users manage a PIN that decrypts the encrypted volume. With TPM, hardware can perform decryption instead of (or in addition to) a PIN. If the storage device is stolen from the computer, it loses access to the TPM and therefore cannot be decrypted.

In addition, BitLocker will not decrypt a volume protected with TPM if it cannot verify the integrity of the device. If an attacker has manipulated the boot-up processes, a process of measurements against expected standards will fail, and TPM will not export the decryption key. This commonly reveals itself to Windows administrators in the form of a recovery key prompt.

Secure Boot

First seen in Windows 8, UEFI’s Secure Boot is familiar to those responsible for a Windows client environment. Secure Boot is used to verify that the bootloaders for the OS are trusted, and not compromised by something like a bootkit. Another capability, Trusted Boot, also protects start-up by continuing integrity checks for system files and drivers, the kernel, and Early Launch Anti-Malware (ELAM), then sending results to the TPM.

Measured Boot

Next in the process, Measured Boot uses audit logs from these processes to report to an attestation server, comparing results against those recognized as being ‘healthy.’ If you manage Windows with Intune, you might benefit from these boot protections without knowing it, as part of device health attestation for device compliance.

Windows Hello for Business (WHfB)

WHfB is the enterprise implementation of Windows Hello and allows users to authenticate using a PIN and/or biometrics. User authentication details are stored locally and don’t transverse the network where attackers can potentially intercept them. As TPM should always be available in Windows 11 devices, WHfB uses the Microsoft Passport Key Storage Provider to store the key in hardware. In OSs that did not mandate TPM, keys could exist in software only.

With the use of TPM, we gain security from its built-in separation of access and protections against brute force. Windows Hello for Business can also be used to satisfy Azure AD MFA requirements: the device itself is regarded as another factor.

Windows Defender Credential Guard (WDCG)

WDCG is our last use case, and this feature uses virtualization-based security (VBS) to isolate secrets held by the Local Security Authority process (lsass.exe), allowing access only through a proxy process. Such secrets include NTLM password hashes, Kerberos tickets, and stored Active Directory domain credentials.

With this isolation, Credential Guard protects against commonly seen techniques where attackers attempt lateral movement and privilege escalation, including Pass-the-Hash. Microsoft uses TPM to supplement Credential Guard, as it can protect the VBS key.

The limits of TPM

It’s important to note that TPM is not a threat protection capability by itself. It integrates with the security features described above to enhance the protection capabilities they provide, primarily through cryptographic checks that allow integrity verification. Malware execution in the OS, for example, would not be blocked by TPM. This includes common tactics such as malicious macros or trojan downloads.

The most notable example may be ransomware. TPM does not stop the encryption of files, and it cannot help the user who falls for a phishing email and hands over their credentials. While TPM can reduce lateral movement within compromised organizations, the reality is that the most common attacks are barely affected by TPM-bolstered features.

Read more: Windows 365 Announced and Azure Virtual Desktop Gains New Features

TPM is Not a Silver Bullet

While it won’t protect against all threats (particularly malware targeted at consumer systems) TPM 2.0 will improve overall device security. BitLocker encryption will protect disk theft against all, but not the most persistent attackers; credential and Windows secrets will be better protected. Point of boot malware, controlled through capabilities such as Trusted Boot, will secure devices before the OS loads.

However, you must consider the trade-offs vs. the potential for unintended consequences. If your device doesn’t have TPM, or if you’re unsupported by Windows 11 due to other requirements like CPUs, you can continue using Windows 10 until its support ends in October 2025. Will we then experience a period of short-term pain for long-term gain?

Potentially, more than a billion Windows 10 devices will need to be replaced over time. Enterprise devices will largely be unaffected, helped by TPM 2.0 as a requirement for official OEM support of Windows since 2016, although the devices might need to enable TPM in UEFI. Purchasing a TPM for older but compatible motherboards is also an option.

Of those billion-plus devices, how many will not be upgraded or replaced and will stop receiving updates, leaving users vulnerable to attacks that Windows 11’s new requirements try to control? How many PCs will be replaced, purely out of necessity to stay on top of patching, creating electronic waste? Remember, Windows 11 has other hardware requirements to factor in, including requiring devices to support VBS and hypervisor-protected code integrity (HVCI).

As organizations consider their plans for Windows 11, the TPM requirement could slow hardware acquisition and deployment because of the need to source specific configurations. TPM is a value-add to any Windows device and does contribute towards mitigating the chain of an attack; however, as has been said a thousand times before – in IT security, there are no silver bullets. TPM simply adds another layer of defense, so don’t expect ransomware, credential compromise, or most endpoint threats to be squashed overnight.

Hello,

I did configure WHFB on test users in our environment but some of them didn’t work as they don’t have TPM (HW) on their machines.

Is there any way to over ride this limitation?

Thanks

the real problem here is MS just obsoleted over a billion devices going against the very long tradition of at least a couple of generations of hardware support all for a questionable security increase . Factor in the stiff hardware requirements and you add how many millions more systems ( home users/laptops ) that have effectively also been obsoleted . Now do the math … 1 billion+ * $ 2000 an average system ( to meets hardware requirement ) and MS with a wave of the collective hand just junked about 2 trillion ( yes trillion ) dollars worth of hardware for what seems some arbitrary and restrictive reasons. And I might add will effectively INCREASE vulnerabilities after 2025 with older win 10 systems … while also going against their own corporate history and tradition of at least a couple generations of prior hardware support.

It is a big D move on MS’s part in my opinion and is just another example of big tech out of control … when one company can dictate/manipulate trillions of dollars in expenditures ( and in this case most of that will be going to china in one way or another ) with zero accountability something is wrong in the tech world.