Microsoft’s GitHub Investment

When Microsoft bought GitHub in 2018, there was a lot of puzzled commentary in the press and in the Microsoft-centric IT world. GitHub was a widely-used but not exactly ubiquitous platform for storing and managing source code, something Microsoft had already implemented in its own Azure DevOps tool, so the puzzlement centered around one question: “Why’d they pay $7.5 billion for that?” As it turns out, Microsoft’s splurge was a really, really good idea, because it positioned them to take a solid lead in the developer tools business. More importantly, it gave them a wealth of data and code to use in training GitHub Copilot, the tagline for which is “Your AI pair programmer.” It was brilliant on Microsoft’s part to position GitHub Copilot (which launched well before any of the other Copilot-branded offerings) as a tool to help a human, rather than a replacement. It’s been very successful in the marketplace, with Microsoft claiming tens of millions of users. More importantly, it’s a well-implemented and useful product.

But Microsoft wasn’t done. GitHub Copilot can help write code for you, either as an agent (where you tell it what to do and it does the whole thing) or little-by-little (where you prompt it to do a specific thing like fix a bug or add a button). You still had to have some programming knowledge to use it effectively. For basic tasks in PowerShell or Python, though, it was hard to beat the utility. However, many problems need solutions that include a user interface, and if you’re not already familiar with UI design tools and coding, Copilot couldn’t help all that much.

Enter GitHub Spark, which Microsoft launched in July 2025. Billed as a tool to “[help] you transform your ideas into full-stack intelligent apps and publish with a single click,” Spark combines Copilot with an interactive preview engine, source code control, and easy publishing.

Spark Requirements

Spark requires a GitHub account, which is free to set up. Spark itself, though, requires that you buy the $39/month Copilot Pro+ package, which includes a base set of 375 “Spark messages” per month. Microsoft’s definition of “Spark message” is pretty vague:

“A Spark message is any prompt you send to Spark to generate or modify your app using natural language. This includes inputs in the Iterate panel or when using targeted editing to adjust specific parts of your app. Each message helps Spark understand your intent—whether you’re adding a feature, refining design, or updating functionality.“

You can’t really tell in advance how many Spark messages it will take to build an app that does what you want, so it’s difficult to answer the question about whether the 375 included monthly messages are enough to do anything useful. Considering that a single message could actually expand to something really complicated, and may run for dozens of minutes, this limit’s probably reasonable. Microsoft’s promised that you’ll be able to buy more messages on a pay-as-you-go basis, but they haven’t implemented that capability yet.

To get started, all you have to do is sign into GitHub Copilot, then tell Spark what kind of app (or “spark”) you want to build.

Getting Started with Spark

You could go read the documentation, but that’s no fun. It’s more fun to start with a prompt. Here’s the prompt I gave Spark for this article:

“Build a simple newsreader that consumes the Practical 365 RSS feed from https://www.practical365.com/feed and allows users to browse articles. The newsreader should show two columns: the left column is a list of articles, and the right column is the text of the selected article. Each article in the left column should show the article title as a clickable URL that, when clicked, loads the article into the right pane. The article object in the left column should also show the article date and author’s name. The left column should show all the items in the RSS feed when retrieved, with a refresh button that reloads it. The right column should display the article text and images. The entire application should be responsive so that it adapts to different screen sizes.”

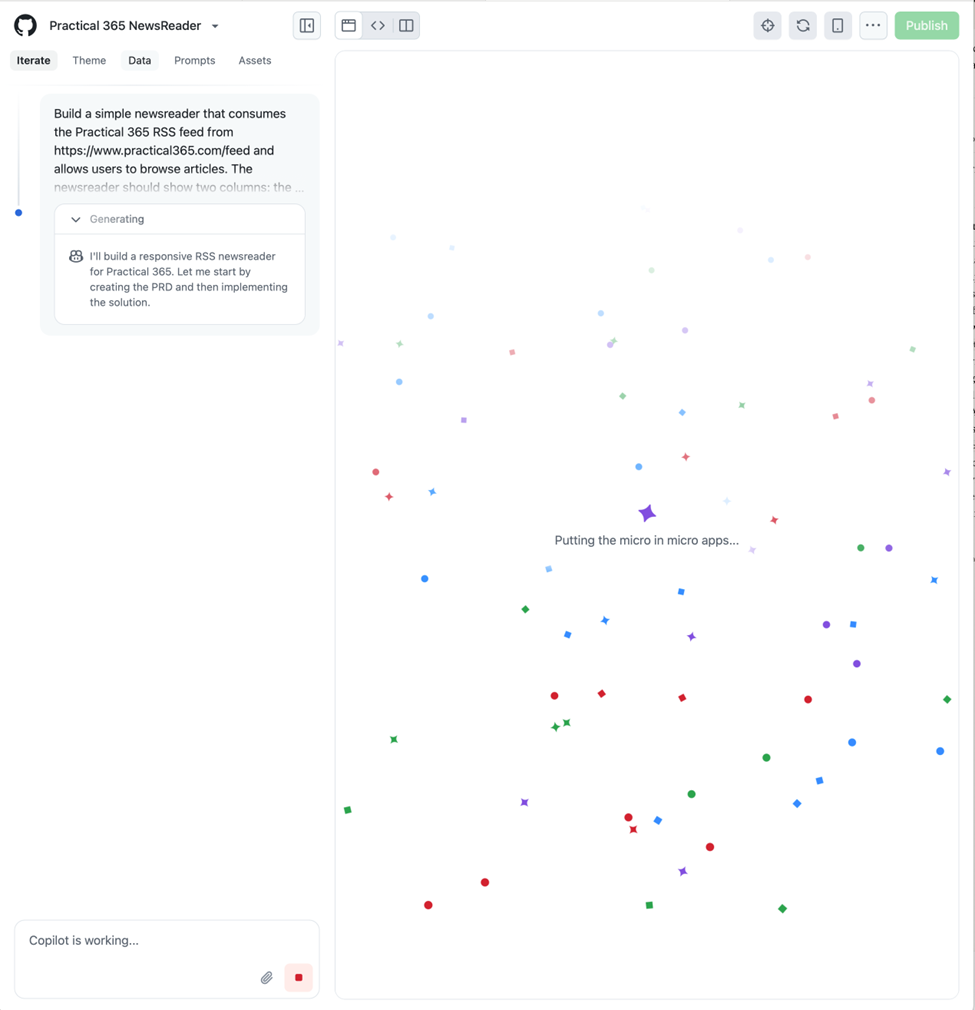

This might seem long and wordy, but as you get experience with AI coding tools, you’ll quickly learn that the more precisely you specify what you want, the more likely you are to get what you want. I fired that prompt off and waited to see what Spark would produce. After about 15 seconds, the prompt disappeared and I got the “real” Spark interface, as shown in Figure 1.

The use of “PRD” here might seem a little weird, but it makes sense once you know that the product requirements document (PRD) is the primary tool for a product manager to tell her team what she wants. The first step in Spark’s work is to take your text prompt and turn it into a pseudo-PRD, then use the requirements from that document to make an agent write the code. After about 7 minutes, Spark had written the PRD and started creating code. The “Generating” widget on the left was periodically updated; for example, as I type this, it now says “Now let me create the article list component.” The generation view periodically refreshes, too.

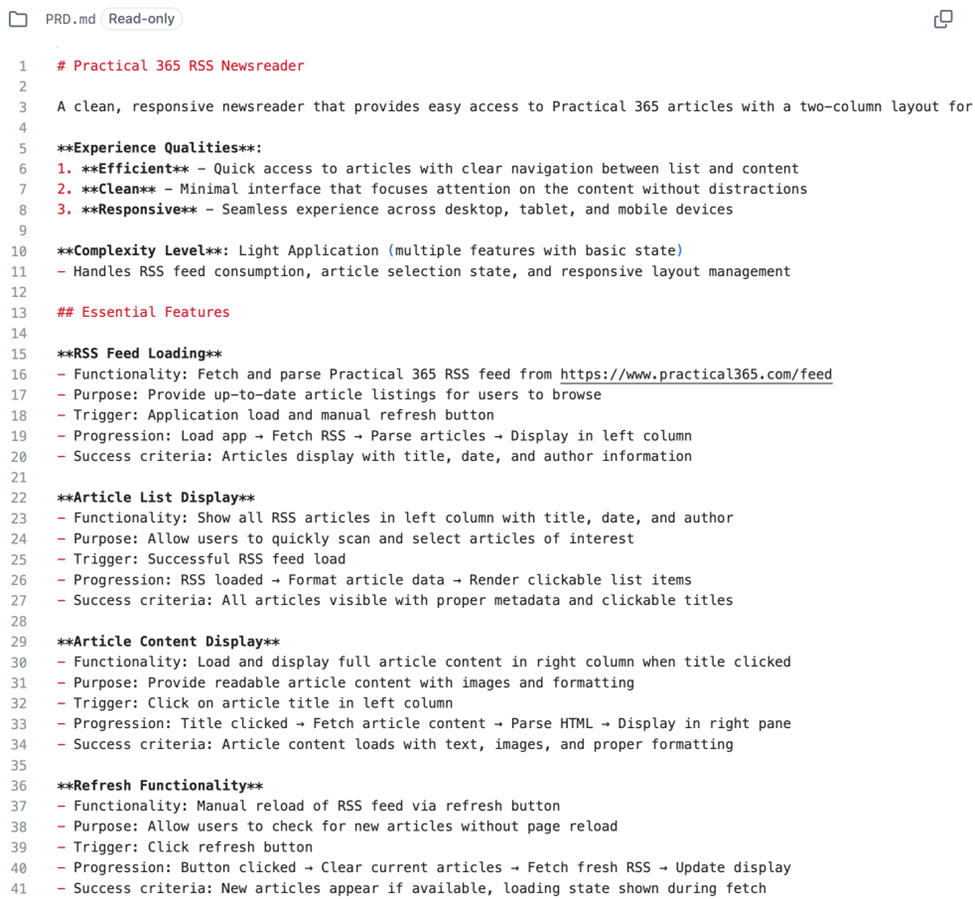

While generation is running, you can click on the name of an item to see it in the code editor, although you can’t edit it. For example, here’s a snippet from the PRD that Spark auto-generated:

As you can see, the initial requirements I gave in the prompt were expanded to include triggers, transitions between states, and success criteria for tests. There are other sections, not shown, that specify the colors, fonts, and animations to be used in the UI.

Sometimes a later step will update the output from a preceding step. For example, about 15 minutes into the build process, Spark decided that it needed to add more text styles for rendering the articles in the right-hand pane, so it updated the index.css file to add those styles.

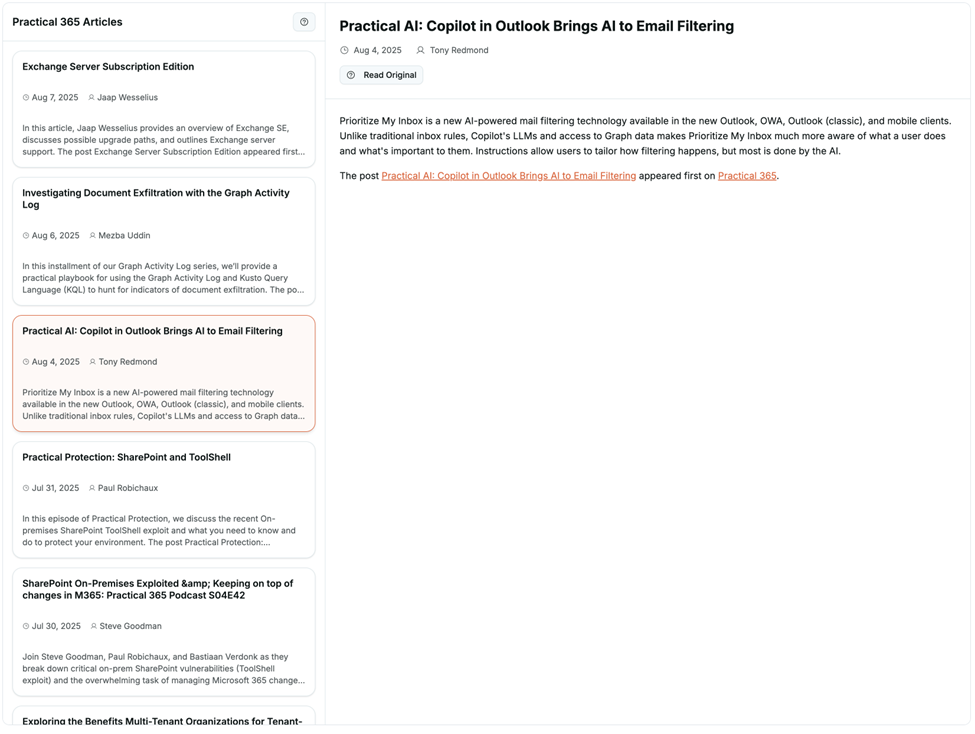

With no input or prompting from me, the generation process finished after 28 minutes. At that point, unfortunately, I kept getting a persistent error message: “Live preview is interrupted. Try refreshing the page to reconnect.” Refreshing the page did nothing. Switching to another browser and reloading the preview, though, produced the spark shown in Figure 3. As expected, if you select an article from the left-hand list, its text is shown in the right-hand pane.

This may not seem like an earth-shattering development; RSS readers are pretty simple. With that said, most people couldn’t write one from scratch in 30 minutes. After another 10 minutes or so of generation, I had added dark mode, article list search, and filtering using the same process: first, Spark updated the PRD, then it used the PRD to decide what else to change, then it made the changes. Don’t forget that all of this responds properly to screen resizing and works properly on mobile browsers, too!

Adding More Customization

Spark wrote all the code and stores it in a familiar-looking tree structure. You’re free to edit any of the files it generates or import them into your own development tools (including the native GitHub code editor or VSCode) to make further customizations. In this case, since the use case for this app was “give me a topic for an article,” I didn’t want to spend any more time editing or customizing it. If I was building an app for actual usage, I could continue to prompt Spark, switch over to giving GitHub Copilot prompts within VSCode, or edit code by hand like some throwback to the 2010s.

You might also find that you need to use GitHub Copilot to fix errors, whether or not you make any changes to the code yourself. While generating the search and filtering UI, the preview stopped with a TypeScript error message and an “Autofix error” button. I clicked it, Spark went off and fixed the error on its own, and code generation continued.

Spark has a number of features that I don’t have space to cover here. For example, Spark will automatically try to integrate with AI-based services (including chatbots) when your prompt or PRD calls for it.

Publishing the Application

You can interact with your spark in preview mode, which is great for satisfying yourself that it works and potentially identifying things that you would want to update or change. When you’re happy enough with the spark to want to share it with others, there’s a big green “Publish” button in the upper right corner of the Spark interface. When you click it, GitHub will publish the spark to the github.app domain, using the name of the Spark as the first portion of the DNS name for the site. By default, the Spark app will only allow you to view the published spark. If you generate a shared link, then anyone who has the link and is signed into GitHub can use the spark. Microsoft has promised to offer a way to allow organization-wide access to apps, which will be a welcome addition. For now, GitHub isn’t charging for deployed sparks, but they do reserve the right to impose capacity limits.

If you’re so happy with your spark that you want to publish it more widely, you can create a GitHub repository and invite collaborators or publish the spark on a “real” cloud platform, such as Azure, AWS, or Google Cloud. This process is pretty straightforward given that the spark is just a TypeScript and React app, which all those platforms (and others besides) support natively.

GitHub Spark vs Power Apps

It turns out that Microsoft already has a platform that seems to promise many of the same advantages as Spark: Power Apps. However, they serve different audiences and use cases. Spark employs an “app-centric” approach where you describe ideas in natural language and immediately see interactive previews you can work with. The output from Spark is TypeScript code that uses the React UI library, just like you’d get if you hired a developer. You manage, secure, and publish it like you would any other React app. By contrast, Power Apps follow a more traditional model where you use visual tools to design the user interface and then connect your UI with Microsoft’s ecosystem; it includes connectors for Dynamics 365, SharePoint, Exchange Online, and Entra ID data. Power Apps also includes a whole application lifecycle management (ALM) toolset to allow you to build, stage, and deploy your Power Apps inside your own enterprise tenant. I tend to think of Spark as like a 3-D printer, which can print anything you can design, while Power Apps is more like a Lego set, with lots of prebuilt pieces you can assemble. You might build a public prototype using a 3-D printer, but you probably wouldn’t show a Lego prototype to your potential customers or investors.

Conclusion

Overall, GitHub Spark is quite useful when you use it as intended: it allows you to go from zero to prototype for simple web applications very quickly. My example app only consumed two Spark messages and was usable, if basic, immediately. I could have spent another dozen messages adding bells and whistles and ended up with something surprisingly useful for a low cost. Best of all, the spark’s in a form that allows me to easily test it, refine it, and share it with others to get feedback if I want to, or I can just publish it directly and use it myself or share it. Although there are other tools that do similar things, Spark is cleanly designed, easy to use, and integrated with the familiar Microsoft ecosystem, so I expect it to become popular quickly.