Sign-in Logs and Audit Records Track User Activity

A reader asked how to report the last app used by individual users. For the purpose of this article, I assume that the intention is to report use of the last Microsoft 365 server app and discounts desktop apps like Office. The question is therefore what data sources are available to query for this kind of information?

Two sources might be useful. The Entra ID sign-in log contains details of apps that user accounts connect to when they authenticate, but Entra ID only retains these records for 30 days. The Microsoft 365 audit log tracks user activity within auditable apps and ingests data from the Entra ID sign-in log. The audit log keeps records for 180 days (with Purview Audit standard licenses) or 365 days (Purview Audit premium), so a longer lookback is possible.

Although neither source is explicitly intended to answer questions of this nature, between the two, we might be able to satisfy the request by using PowerShell to retrieve data and to stitch everything together. Let’s explore some of the ways to answer the question.

Targeting User Accounts to Report

The first decision is to select the set of accounts to report. Not every Entra ID account is created equal. Even within member accounts (belonging to the tenant), there are user accounts in daily operation, utility accounts created for administrative purposes such as break glass accounts, and accounts that often don’t have any licenses such as those created for shared and room mailboxes.

The assumption is that the set of target accounts are enabled member accounts with licenses. A filter is required to extract the target set of accounts from Entra ID. Here’s the command I used:

[array]$Users = Get-MgUser -All -PageSize 500 -Filter "usertype eq 'member' and accountenabled eq true and employeeType ne 'Utility' and assignedLicenses/`$count ne 0" -Sort displayName -ConsistencyLevel Eventual -CountVariable Count -Property DisplayName, UserPrincipalName, id, employeeType, userType, accountEnabled

In a nutshell, the command finds licensed member accounts that are enabled and the employeeType property not set to “Utility.” Because Entra ID doesn’t distinguish between accounts used by humans and those used for housekeeping or other administrative purposes, it’s a good idea to leverage the employeeType property.

The employee type, employee hire date, and employee date properties are relatively recent additions to Entra ID, so for historical reasons some tenants assign a value like “XXX” to the Office property to mark utility accounts. It doesn’t matter what method you use if the property supports server-side filtering. Using efficient filtering doesn’t matter in small tenants, but it becomes hugely important as the number of accounts increases.

After finding the user accounts to process, the next step is to retrieve some data to report.

Fetching Audit Sign-in Logs

For Entra ID sign-in logs (an Entra P1 license is required for API access to these logs), the code calls the Get-MgAuditLogSignIn cmdlet to find the first three sign-in records matching the user account identifier. Each of the sign-in records notes the application that the user connected to in the AppDisplayName property, so that’s what the script captures together with the timestamp for the latest sign-in record:

$UserId = $User.Id

[array]$Logs = Get-MgAuditLogSignIn -Filter "UserId eq '$UserId'" -Top 3

If ($Logs) {

[array]$AppNames = $Logs.AppDisplayName | Sort-Object -Unique

$LastAppSignIn = $AppNames -join "; "

$LastAppSignInDate = Get-Date ($Logs[0].CreatedDateTime) -format 'dd-MMM-yyyy HH:mm:ss'

}

It’s entirely possible that no sign-in records will be found for users. By definition, a sign-in record is only captured when a user signs into Entra ID and the records are only available for 30 days. If someone has been absent for some reason, they might not have signed in for more than 30 days. Or if an app doesn’t need to sign in because of durable credentials, there might not be any trace of a sign-in to find.

Fetching Microsoft 365 Audit Records

Because we can’t rely on finding a sign-in record for an account, the script also checks the Microsoft 365 audit log. This code snippet shows how to find the three most recent audit events using the Search-UnifiedAuditLog cmdlet. Once again, some post-processing is performed to extract the information to report.

[array]$AuditLogs = Search-UnifiedAuditLog -StartDate (Get-Date).AddDays(-90) -EndDate (Get-Date) -UserIds $UPN -ResultSize 3 -Formatted

If ($AuditLogs) {

[array]$AuditLogApps = $AuditLogs.RecordType | Sort-Object -Unique

[array]$AuditLogActions = $AuditLogs.Operations | Sort-Object -Unique

$AuditLogTimeStamp = Get-Date ($AuditLogs[0].CreationDate) -format 'dd-MMM-yyyy HH:mm:ss'

}

Some additional work is done to turn the audit record type into a more understandable format. The record type defines the workload that generated an audit record. At the time of writing, there are 391 different audit record types, which speaks to the vast array of information hoovered up in the audit log.

Reporting the Findings

After the processing of sign-in and audit data completes, an item for an account in the report data looks like this:

UserPrincipalName : tony.redmond@office365itpros.com Name : Tony Redmond LastAppSignIn : Office 365 SharePoint Online; Office365 Shell WCSS-Client LastAppSignInDate : 27-Aug-2025 13:30:13 AuditLogApp : Exchange Online, SharePoint Online AuditLogAction : CopilotInteraction, FileAccessed, MailItemsAccessed AuditLogTimeStamp : 27-Aug-2025 18:38:00

This data might need a little more cleanup, such as making the app names used in sign-in logs more recognizable (perhaps using the method described in this article), but the report contains enough information to answer the original question. The problem is that generating the data takes time.

A Question of Performance

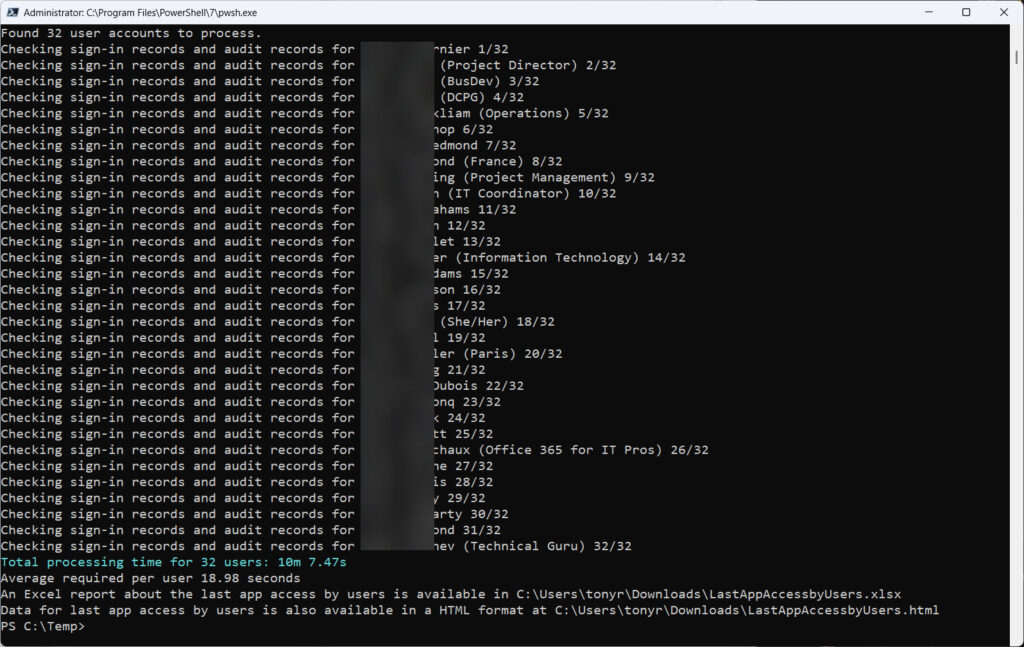

As I started to experiment with fetching audit data, I discovered that the script needed an extraordinary amount of time to fetch data for each account. Figure 1 shows that processing each account took an average of over 18 seconds. The time required depends on many factors, notably service load, and the highest I saw was 23 seconds. Running per-account searches against the Entra ID and Microsoft 365 audit logs took most of the time, with the Entra ID searches taking longest.

This discovery prompted me to make some changes to the script to allow it to avoid searching the Entra ID logs. Instead, the last sign-in data came from the signInActivity property for user accounts. This information doesn’t include the app that the user signed into, but removing the check against Entra ID reduced the time per account down to 1.5 seconds.

Then someone in Microsoft must have discovered a performance problem with Entra ID because suddenly searches started to work much faster. Including the Entra ID lookup now required approximately 5.5 seconds per user account.

Even the improved performance is unacceptable for large tenants. Taking five or so seconds to discover the last app accessed by a user is acceptable when relatively few accounts are involved. It is a different matter when thousands of accounts must be checked. At that point, running the script interactively becomes an exercise in waiting.

The Microsoft 365 audit log ingests events from Entra ID, meaning that it’s possible to search the audit log to find sign-in events. To check if this would be a solution, I considered this code to find the sign-in records for an account over the last 30 days. The code removes duplicates from the returned set and sorts the records in descending date order:

[array]$Records = Search-UnifiedAuditLog -StartDate (Get-Date).AddDays(-30) -EndDate (Get-Date) -Formatted -SessionCommand ReturnLargeSet -ResultSize 5000 -Operations UserLoggedIn -UserIds Ken.Bowers@office365itpros.com

$Records = $Records | Sort-Object Identity -Unique

$Records = $Records | Sort-Object {$_.CreationDate -as [datetime]} -Descending

Unhappily, the audit data payload for the records doesn’t include the app name. Although audit log records have some common properties, the decision about the information to include in the audit payload is left to each development group, and in this case, it seems like the Entra ID team decided that the app information captured in their sign-in records should not be brought forward to the audit log.

Using Azure Automation to Run the Job

A practical solution to running jobs that take a long time is to use Azure Automation (please avoid the temptation to use the insecure Windows Task Scheduler instead). The PowerShell code will run quite happily in a runtime environment, and the only remaining question to solve is how to get the report back to administrators. The simplest method is to send the files as attachments to an email, but the files could also be uploaded to a SharePoint Online site or posted to a Teams channel.

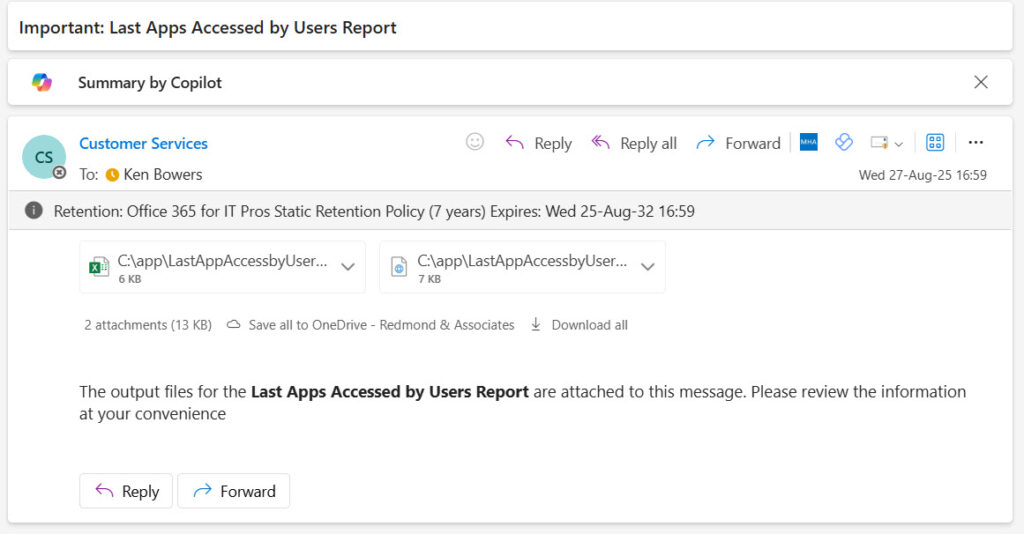

Naturally, I elected to use the easiest method and added the necessary code to create and send a message using the Send-MgUserMail cmdlet. The message (Figure 2) has two attachments – a HTML format report and a CSV file or Excel worksheet containing the raw data. An Excel worksheet is created if the ImportExcel module is loaded as a resource into the automation account.

The normal rules for Azure Automation apply for this runbook: make sure that the service principal for the automation account is assigned the correct Graph permissions (User.Read.All, Mail.Send, and AuditLog.Read.All) and that the requisite sub-modules of the Microsoft Graph PowerShell SDK are loaded as resources for the automation account.

Because the script uses Exchange Online PowerShell, the service principal for the automation account must also be assigned the Exchange administrator role and be assigned the Exchange Online “Manage Exchange as application” permission (see this article for details).

Feel Free to Improve the Script

The complete script can be downloaded from GitHub. The nice thing about PowerShell is that it’s so flexible, so enjoy thinking about how you’d solve the problem. Feel free to suggest enhancements or different approaches in the comments for this article, or create a GitHub pull request with updated code that you think should be in the script. One thing’s for sure. The data exists to answer the question, but unless the data has been pre-processed (for example, by extraction to an external SIEM), it will take time to extract the information from Microsoft 365.